A success story of a Facebook group

Csillagászat-kedvelők (Astronomy Enthusiasts) is a Facebook group that I created in the summer of 2012 to share astronomy-related articles, news, and other things with my friends who are interested in astronomy. There were plenty of them: at the time I was studying astronomy at ELTE, and I was known to many people in amateur astronomy circles. Back then, I never imagined that 12 years later there would be 30,000 people in the group. After the group was created, we grew in number, and people I didn’t know wanted to join, and they weren’t necessarily people involved in astronomy, in fact: they were mostly completely average Facebook users who found the group for some reason. It’s not a big deal, all Facebook groups work like this. But instead of a group of friends who were more or less familiar with astronomy, I immediately found myself in a social media bubble: toxic commenters, swearing, pseudoscience, posts with unqualified spelling one after another, etc. It was possible to hire administrators and moderators back then, who helped with moderation, but that was just one thing. I think the most important thing was to lay down the basic principles of the group. We had to experience how much it was worth getting into a debate with someone, and how tolerant we should be towards unscientific things – because it’s okay to write posts like „I saw a UFO” with fire and iron and zero tolerance, but what about when it’s just an educational article full of sloppy wording? The rules of the group slowly developed, and in the meantime there were changes between administrators and moderators from time to time. (Communication between equal leaders, for example, would definitely be worth a separate post.) We had to determine what values we wanted to represent in the group. Scientific credibility: The primary principle is credibility. I think the standard is extremely high. There is a national news portal from which we almost never allow articles because we do not consider the articles published there to be credible. (Despite this, we always start reading it, but it turns out pretty quickly that it is tabloid, clickbait, and does not reach the standard that we would like to see in the group. Creating a cohesive community: This principle covers quite a lot. It’s not just about group members writing to each other respectfully and constructively. It is especially important to help beginners, because it often happens that an enthusiastic interested person writes something stupid or sends a very basic post. It is important that in such cases they are not embarrassed. We give advice and answer their questions, even if they are very basic, this is natural. It also includes the fact that we do not laugh at pseudoscientific things at all. There are many groups where people interested in science make esoteric teachings and their practitioners a target of ridicule. For me, and for the group, this is not correct behavior. I see that if someone falls victim to their own naivety and esoteric teachings, it is misery enough for them, there is no need to be the object of hatred. Enforcing these principles has at one time brought about quite a few conflicts, which I had to learn to deal with. However, there has been no precedent for these for years, which is partly due to the power of the community (experience shows that if an existing community behaves in a certain way, new members most often adapt to it), and partly to the fact that I am no longer affected by the curses of others, especially since I see the results of consistency and standing up for principles. Thanks to these principles, things have emerged in the group that were not intentionally created, but are the result of the right community: Due to the scientific credibility and the relaxed environment, many professional astronomers and very knowledgeable amateur astronomers are active members of the group. It regularly happens that a curious, lay person’s questions are answered by a professional astronomer, so they receive the most professional answer possible. A high-quality discourse develops under the articles and news published in the group, which is not at all typical of the pub talk in the comment section that is typical of the rest of Facebook. Experienced amateur astronomers submit world-class observations. These experienced amateur astronomers also help beginners. Several telescope shops and other astronomy-related businesses are also represented in the group, they are active from time to time and give advice on buying telescopes. I am especially glad that it is not typical for any of the store employees to start bidding on each other to buy their products. The group also hosts a number of astronomical events – I’m not talking about a single phenomenon here, but telescope demonstrations related to the phenomenon, but there are also camps, personal and online lectures, etc. that reach more people. In recent years, the group has basically been characterized by consistent daily maintenance. Dealing with the group is part of my morning routine, I usually deal with it while sipping my coffee: Sharing some astronomy articles and news Checking out new applicants and posts waiting for approval Reading the comments and making sure everything is in order. Moderating Changing the cover photo There are seven of us in the admin/moderator team, and it also takes the consistent work of the others to make it all work. Occasionally, Facebook introduces features that can be useful to us: for example, the “Expert of the Group” designation. We were able to mark if someone is a professional astronomer or has enough astronomical knowledge to be sure that they are writing something scientifically credible – but I don’t think anyone does this. In any case, whenever a new feature is released, we definitely try to test how it can be useful to us. Who knows when a feature will come along that will bring a big breakthrough. Of course, there are possibilities, I am also

Power BI HRD

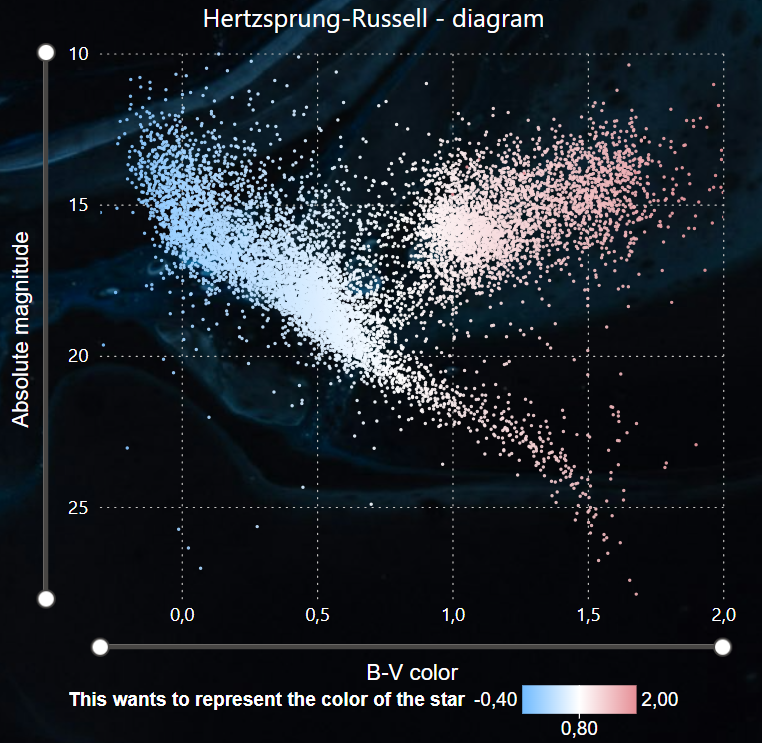

In order to achieve my long term career goals, I really need to learn how to use Power BI. Since self-study is my superpower, I added it, and to add some fun, I used astronomical data. I downloaded the Hipparchos catalog as a test, and based on the contents of the columns I realized that a Hertzsprung-Russel diagram (HRD) would be perfect for my first project. This chart, which is fundamental to astronomy, was also a great project because there were so many different things to try and learn about Power BI. However, to be honest, my initial goal was just a simple HRD, the other filters, slicers and other features were just additional ideas. I did not regret this project at all, in fact, I really enjoyed the work. My HRD HRD represents the absolute magnitude of a star as a function of its color, but before we can proceed further, I need to define both terms first. Absolute magnitude Color of a star (B-V) Anyone who has seen a starry sky has noticed that the stars appear to be of different brightness. This is the visual magnitude. However, how bright a star appears depends on many different factors: From the brightness of the star: as they are also physically different. From the distance of the star: by definition, since a star is further away, the fainter it appears. From light absorption. We had no data on light absorption, and compared to the other two factors, it affects the magnitude of the star very little. So we neglect this. If we want to know how bright the stars really are relative to each other, we have to calculate how bright they would be if they were the same distance apart. The magnitude, which would be the apparent magnitude (m) of the star at a distance of 10 parsecs, is called absolute magnitude (M). The relationship between the two quantities is in the Function 1, where d is the distance to the star in parsecs. Stars have different colors, just like light bulbs have different color temperatures. To express this, the color index (most often the B-V color index) is used in astronomy. The physical details of this are beyond the scope of this article, so let’s stick with the fact that the color indices are usually in the range between -0.5 and +2. Smaller numbers are the color index of stars with a bluer, therefore higher color temperature, while larger numbers refer to a redder color. Function 1: Relation between the apparent and absolute magnitudes. The Hipparcos catalog contained many columns. When interpreting this data, I realized that not only can I display an HRD based on the data, but later I will be able to make it more interactive and informative with slicers. Since at this point I couldn’t assess exactly what I could get out of this project, I imported most of the database columns into PowerBI. The Hipparchus catalog did contain the B-V color index, but not the absolute magnitude of the stars, only the apparent megnitude. The absolute magnitude had to be calculated, but the database also did not contain the distance of the stars. Parallax, however, does. In general, parallax is the change in the relative position of bodies at different distances, viewed from different directions. The stars appear to move minimally as the Earth revolves around the Sun, and the distance can easily be calculated from the angle of this displacement. Due to the small angular deviation, the trigonometric parts of the formula can be neglected. The relation is therefore the following: Function 2: relation between parallax and distance Once the distance has been calculated from the parallax, the absolute magnitude can also be calculated from the apparent magnitude. So we have the two physical entities required for HRD. Picture 1: HRD generated with Power BI After I tried everything related to editing HRD from a design point of view, I was already thinking about how I could make it more useful, interactive and informative. Spectral type slicer On the HRD, the different types of stars are located separately, in their specific places. Of course, stars can be grouped in several different ways, which may be interesting from our point of view. I looked through the columns of the Hipparchus catalog and to my great delight it contained the spectral type of the stars. The spectral type is essentially an identifier consisting of a few characters, the different characters of which have different meanings. The first character can typically be a letter (O, B, A, F, G, K, M, R, etc.), while the second character can be its subcategory from a data visualization point of view. So I dreamed up a two-level slicer to mark the spectral type. However, I ran into some difficulties here: The spectral type can really be very diverse. It wasn’t given for every star, there were also empty lines. There were cases where the data was enclosed in parentheses or where the second character was a “/” or “+” sign. There were cases where only the bottom character appeared, etc. So I excluded empty lines and spectral type data starting with special characters from the analysis. I suppose this is a regular complication for anyone who works with Power BI on a daily basis, but this is the first time I’ve encountered this problem. Picture 2: And here’s the slicer. In the picture, I filtered it to the G2 stars, the HRD changes dynamically accordingly. Stellar classes The stellar classification does not end with spectral types, in fact, the best part is just beginning. The Roman numeral following the first two characters of the spectral type indicates the classes of the stars, which is so interesting, and they appear so typically on the HRD that it would have been a mistake to make a three-level slicer for the spectral types. Only these Roman numerals deserved a separate button slicer. I could write about stellar evolution and star classification for an amazingly long time, but this again goes beyond the scope